The NGI Policy Summit hosted a series of policy-in-practice workshops, and below is a report of the session held by Edgeryders, written by Amelia Hassoun, Leonie Schulte and Kate J. Sim.

The EdgeRyders NGI Ethnography Team is dedicated to responding to three core, intersecting questions: when people talk about the future of the internet, what are their key concerns and desires? What issues do they face, and what solutions do they imagine? And how can we, as ethnographers, visualise and analyse these topics in a way that meaningfully contributes to ongoing debates and policy-making?

At the 2020 NGI Policy Summit, we demonstrated how we responded to these questions through digital ethnographic methods and qualitative coding.

As digital ethnographers, we participate in and observe online interaction on EdgeRyders’ open source community platform, engaging with community members as they share their insights on issues from artificial intelligence, to environmental tech, to technology solutions for the COVID-19 pandemic.

We also code all posted content through Open Ethnographer; an open source coding tool that enables us to perform inductive, interpretive analysis of written online content. In practice, this means that we apply tags to portions of digital text produced by community members in a way that captures the semantic content of online interactional moments. This coding process yields a broader Social Semantic Network (SSN) of codes that allows us to gain a large-scale view of emerging salient topics, while being able to zoom in to actionable subsets of conversation.

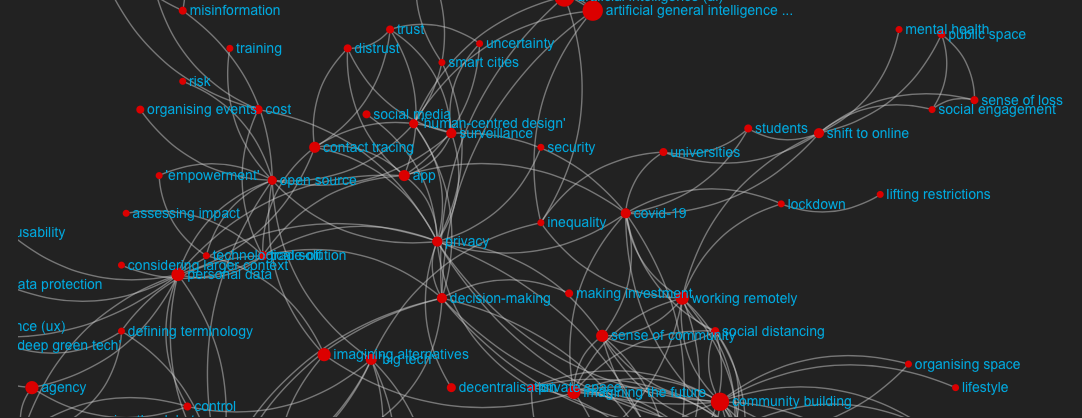

We visualise and navigate this ethnographic data using the data visualisation tool, Graph Ryder, which adds a quantitative layer atop our qualitative approach to data collection. Graph Ryder gives us a visualisation of all generated codes, allowing us to trace co-occurrences between codes and see code clusters, which show us what concepts community members are associating with each other. This approach shows us who is talking to each other, and about what topics, across the entire platform. During our workshop, we invited attendees to explore Graph Ryder with us. Here are some examples we used:

We find interesting co-occurrences when filtering the graph to k=4. For those unfamiliar with our tool, Graph Ryder, this means that we are looking at connections between codes that have been mentioned together by community members at least four times.

At this level, we can see some broad themes emerging as we look at the graph as a whole. We can then zoom in on a code like “privacy”, an extremely central node in the conversation among community members. This code is linked to other codes like “personal data”, “trade-offs”, “cost”, “surveillance” and “decision-making”. These connections, in turn, create an illustrative network of privacy concerns articulated by the community: around smart cities and human rights, covid-19 and contact tracing, trade-offs and decision-making. A salient theme is the question of how to weigh up privacy trade-offs, in order to make optimal decisions about one’s own data privacy. What does it cost? There is uncertainty around how extensive surveillance is, and a distrust of the information that one is given about these technologies, which makes making quality decisions about these issues difficult for community members.

Social Semantic Network Analysis combines qualitative research at scale with participatory design: we can, thus, dynamically address what people know, what they are trying to do and what they need. It also affords us a great deal of foresight, meaning we can look towards the future and identify what might be brewing on the horizon.

So, how does this method allow us to inform policy? The digital ethnographic approach means we are continuously engaging with a broad range of individuals and communities across Europe; from activists to tech practitioners and academics, among many others. This gives us unique access to viewpoints and experiences that we can, in turn, explore in greater detail. This approach combines the richness of everyday life details gained through ethnographic research with the “big picture” vantage point of network science. Our inductive approach to community interaction means we remain open to novelty: allowing us to address problems as they emerge, without having to define what those problems are from the outset.