By Katja Bego, principal investigator NGI Forward

Today, we are launching our new report Towards Public Digital Infrastructure: A proposed governance model. You can read more about earlier iterations of this work in our NGI Forward vision paper, and blog on open strategic autonomy.

On today’s internet, power is concentrated in the hands of a handful of actors who

increasingly control what we read and what we see. We live in a winner-takes-all

digital economy, where the tendency tends to be towards ever more concentration, both

within and across layers of the technology stack. The battle for domination is

increasingly also a geopolitical one, with the internet a central playball in the

current tide of resurgent Great Power conflict. Attempts by both governments and large

technology companies to take back control are an important source of internet

fragmentation – recent events have us teetering closer to the splinternet than ever

before – and leave citizens with little agency and choice.

Many

around the world have looked to Europe to provide an alternative vision to these

top-down approaches, and the rather reductive Beijing versus Silicon Valley binary

that increasingly drives it. But if the EU wants to shape a real alternative it needs

to change its approach. Europe’s role as a regulatory superpower has been

much-praised, but it has also increasingly become clear that harnessing the so-called

Brussels Effect, the EU’s ability to influence global norms and regulation, remains

limited to softening the hardest edges of the existing digital economy, but has little

generative potential on its own. Europe cannot just remain the global referee, but

also needs to create alternatives of its own by becoming a market-shaper, rather than

remaining a market-taker. The Commission’s current open strategic autonomy efforts and

NextGenerationEU funds reflect this ambition, as does the development of a bold set of

new legislation, notably the DSA, DMA and DGA, which are set to write the rules for

the digital economy for decades to come.

These ambitious initiatives need to be put at the service of setting out a compelling and tangible vision for a more resilient and open future internet. Europe now has the momentum and opportunity to take the lead in imagining new institutions that can deal with the unique challenges digitisation has brought to the fore. Now is the moment to become more deliberate about using the levers of government strategically to generate sustainable, interoperable ecosystems in which alternative solutions can thrive.

As the European Commission seeks to give shape and meaning to its objective of achieving open strategic autonomy, and articulate a compelling alternative vision in an increasingly (geo)politicised global technology arena, it needs to ensure it promotes an internet model that is based on openness and diversity, and champions the public good, and encourages like-minded peers around the world to join these efforts. This paper aims to set out a new framework to do just this; a new model that would seek to redistribute power over the internet by building a more vibrant, diverse and resilient ecosystem of trustworthy open solutions on top of shared set of rules and open protocols and standards. We will refer to this model as Public Digital Infrastructure (PDI).

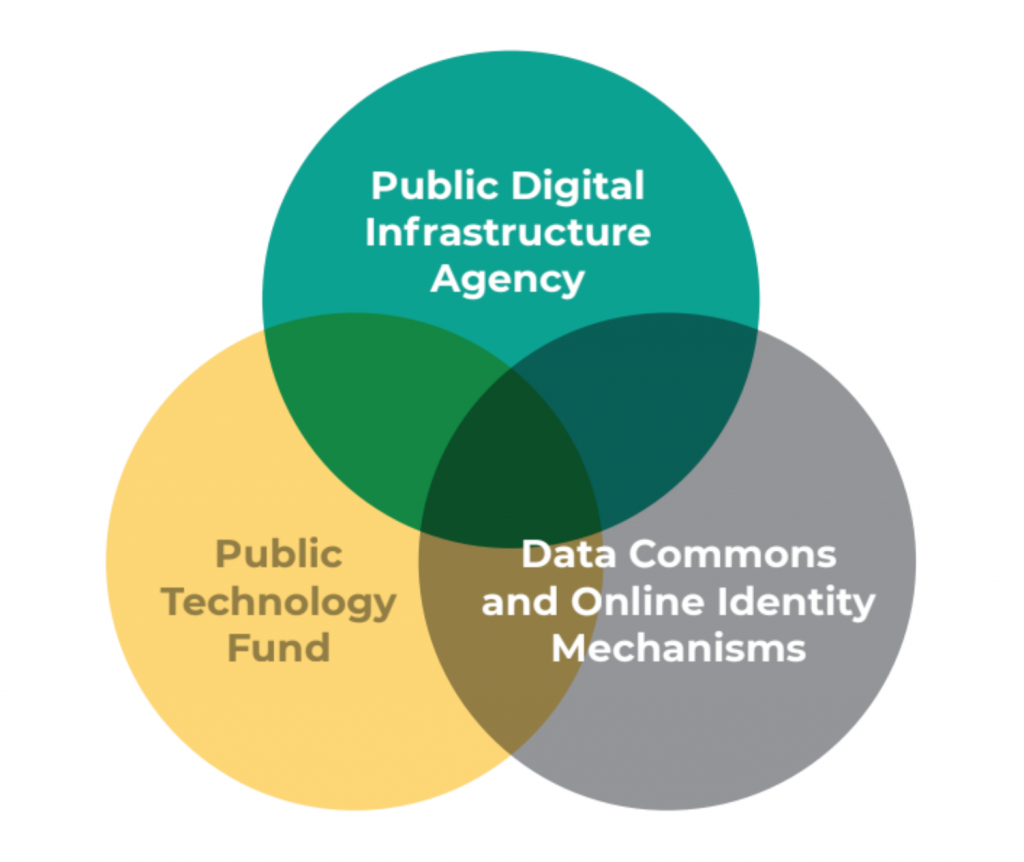

We already have the technical and governance building blocks at our disposal to make this Public Digital InfrastructureI model a reality. We also have the political momentum on our side through a number of ambitious policy proposals and funding agendas on the European level. The challenge now is to integrate these building blocks into a single cohesive system, and to ensure we put into place the right institutions and rules to ensure the DPI can achieve trust, scale and openness. This approach is made up of three key pillars:

-

Generating an ecosystem of healthy, interoperable alternatives:

Public Digital Infrastructure could help us move away from a platform economy, where one actor owns a whole suite of tools and can unilaterally set the rules, towards a protocol-based economy, in which we could see a collaborative ecosystem of smaller, interoperable solutions and applications emerge, built on top of a shared set of rules and open protocols. We could see this as an alternative, parallel infrastructure, made up of open, trustworthy solutions and public goods. Through collaborative interoperability, solutions built on top of the Public Digital Infrastructure would proactively set out to integrate their solutions with other tools built on the framework.

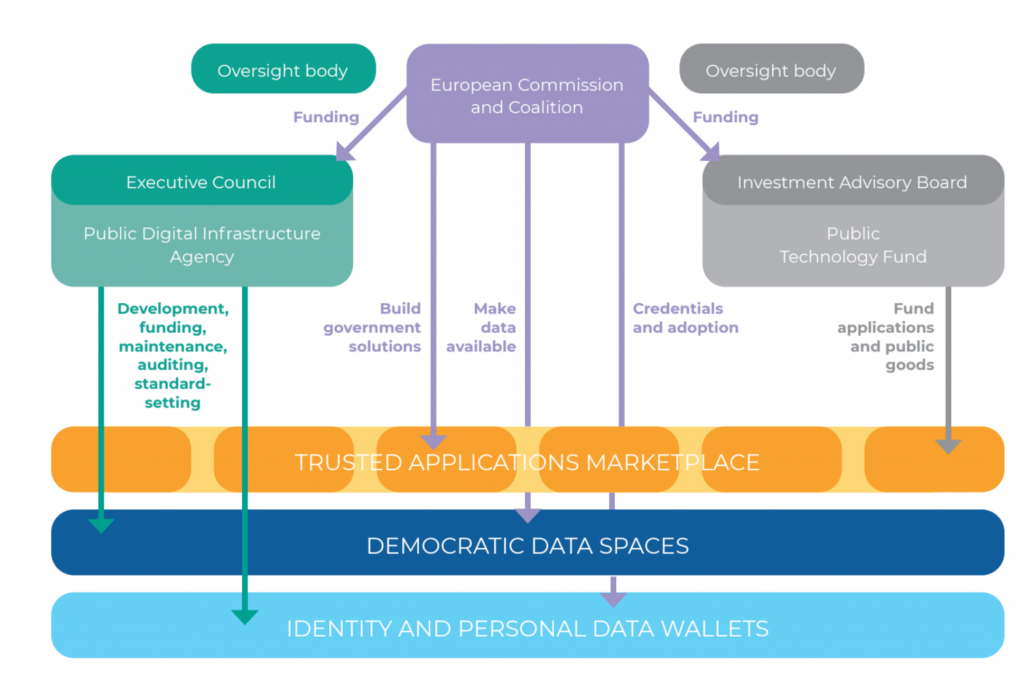

To help this ecosystem thrive, the Commission and other governing bodies (from the local level to the supra-national) would seek to leverage their own market shaping-levers, for example through strengthening rule-setting through procurement, and moving their own solutions on top of the system. The European Commission would further provide the funds for an independent Public Technology Fund, which would support the development of applications on top of the Public Digital Infrastructure, as well as fund public goods to support the wider ecosystem.

- Designing governance models fit for purpose: No single centralised entity – public or private – would control the underlying Public Digital Infrastructure model; instead, the system would be governed on the basis of a shared set of rules and protocols for, for example, interoperability, data sharing and online identity management. In this model, civil society, trusted public institutions, academia, and the public-interest technology community would be empowered to collaboratively shape the rules, standards and governance models underpinning this shared logic.

To ensure these decision-making processes remain open and representative, but also

geared towards effective decision-making, the European Commission would provide the

funding for the establishment of a fully independent

Public Digital Infrastructure Agency, tasked with bringing together

the community, and providing resources for maintenance and auditing of the PDI’s

components.

- Opening up data and identity: Every internet user would be provided with the means to control their own digital identity and personal data online, empowering them to share what they want, with whomever they want, on their own terms. To do this, each user of the Public Digital Infrastructure model would have the right to be issued their own portable online identity and personal data wallet, which would allow them to share and pool data on a case by case, consent-based basis.

Developers of applications and services would be able to tap into the user-generated data commons that would result from this pooling in a way that is accountable and fair, rather than feel compelled to amass their own proprietary data lakes in order to compete. We should not imagine these commons as one single enormous, distributed data lake, but rather as a set of data governance mechanisms, ranging from data commons to trusts, which would be employed and governed depending on the use case and sensitivity and utility of the data at hand. Users would be able to pick and choose which commons to participate in, and solutions would contribute to these commons as a condition of being part of the PDI.

Figure 1: Three ingredients of the Public Digital Infrastructure framework

By redistributing power over technology, rather than seizing it, Europe can empower internet users around the world to benefit from and participate in the digital economy on their own terms, while also championing its own, alternative vision – a vision built on ideas of openness and pluralism – to compete with the reductive Shenzhen versus Silicon Valley dichotomy. Because rather than trying to build the next Google or WeChat, should we not focus on building the infrastructures that prevent the next Google and WeChat instead?

Figure 2: Public Digital Infrastructure visualised

1 Bego, K. (2020). A Vision for the Future Internet – A Roadmap.

2

Ibid.

3 https://www.nesta.org.uk/feature/10-predictions-2017/the-splinternet/ ;

https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/03/17/1047352/russia-splinternet-risk/

4

Bradford, A. (2012). The Brussels Effect. Northwestern University Law Review, Vol.

107, No. 1, 2012, Columbia Law and Economics Working Paper No. 533, Available at

SSRN: https://ssrn.

com/abstract=2770634

5

https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/digital-services-act-package

6

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20220315IPR25504/deal-on-digital-markets-act-ensuring-fair-competition-and-more-choice-for-users

7

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020PC0767

8

https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2021/february/tradoc_159434.pdf