We’re introducing each of our four Policy-in-Practice Fund projects with an introductory blog post. Below, Sophie Bloemen and Thomas de Groot from Commons Network, and Paul Keller and Alek Tarkowski from Open Future, answer a few of our burning questions to give us some insight into their project and what it will achieve. We’re really excited to be working with four groups of incredible innovators and you’ll be hearing a lot more about the projects as they progress.

Can you explain to us what you mean by interoperability, and why you think interoperability could be an effective tool to counter centralisation of power in the digital economy?

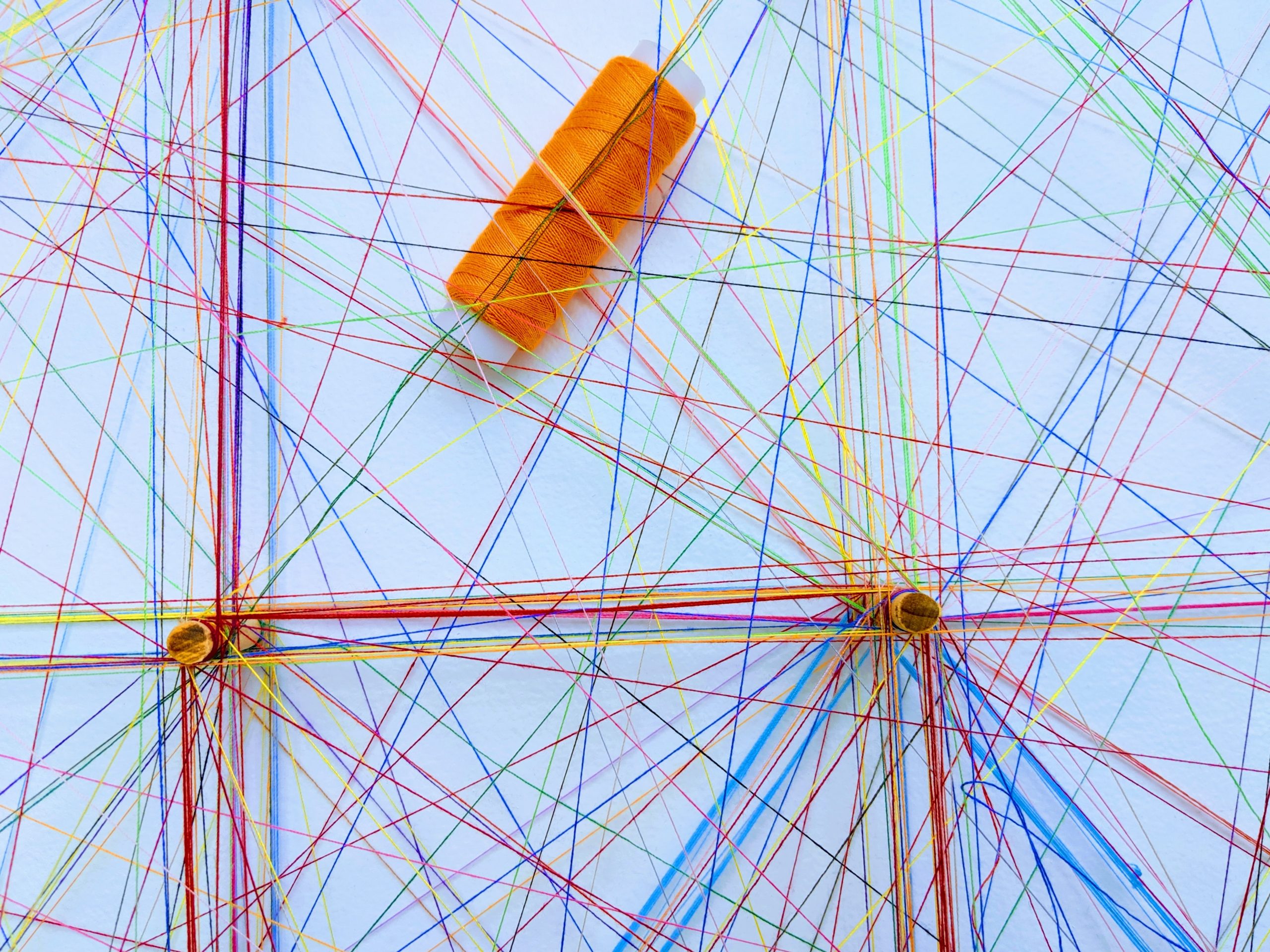

Simply put, interoperability is the ability of systems to work together and to exchange data easily. In policy circles today, the term is mostly used as a solution to the structurally unhealthy dominance of a small number of extremely large platform intermediaries that is increasingly being understood to be unhealthy, both socially and politically speaking.

In the case of Facebook, for instance, introducing interoperability would mean that a user could connect with Facebook users, interact with them and with the content that they share or produce, without using Facebook. This would be possible because, thanks to interoperability, other services could connect with the Facebook infrastructure.

This scenario is often presented as a way of creating a more level playing field for competing services (who would have access to Facebook’s user base). In the same vein, proponents of interoperability argue for an ecosystem of messaging services where messages can be exchanged across services. This is also the basis of the most recent antitrust case by the US government against Facebook. At the very core, these are arguments in favour of individual freedom of choice and to empower competitors in the market. We call this approach competitive interoperability.

While this would clearly be a step in the right direction (the Digital Markets Act proposed by the European Commission at the end of last year contains a first baby step, that would require “gatekeeper platforms” to allow interoperability for ancillary services that they offer but not for their main services) it is equally clear that competitive interoperability will not substantially change the nature of the online environment. Increasing choice between different services designed to extract value from our online activities may feel better than being forced to use a single service, but it does not guarantee that the exploitative relationship between service providers and their users will change. We cannot predict the effects of increased market competition on the control of individual users over their data. In fact, allowing users to take their data from one service to another comes with a whole raft of largely unresolved personal data protection issues.

We see interoperability as a design principle that has the potential to build a more decentralised infrastructure that enables individual self-determination in the online environment. We propose to call this type of interoperability generative interoperability.

So, even though there are limits on this particular idea of interoperability, this does not mean that the concept itself has no use. Instead, we say that it needs to be envisaged with a different purpose in mind: building a different kind of online environment that answers to the needs of public institutions and civic communities, instead of ‘improving markets’. We see interoperability as a design principle that has the potential to build a more decentralised infrastructure that enables individual self-determination in the online environment. We propose to call this type of interoperability generative interoperability.

What question are you specifically trying to answer with this research? And why is it important?

In our view, the purpose of generative interoperability must be to enable what we call an Interoperable Public Civic Ecosystem. And we are exploring what such an ecosystem would encompass, together with our partners. We know that a public civic ecosystem has the potential to provide an alternative digital public space that is supported by public institutions (public broadcasters, universities and other educational institutions, libraries and other cultural heritage institutions) and civic- and commons-based initiatives. Can such an ecosystem allow public institutions and civic initiatives to route around the gatekeepers of the commercial internet, without becoming disconnected from their audiences and communities? Can it facilitate meaningful interaction outside the sphere of digital platform capitalism?

This experiment is part of the Shared Digital Europe agenda. Could you tell us a bit more about that agenda?

Shared Digital Europe is a broad coalition of thinkers, activists, policymakers and civil society. Two years ago we launched a new framework to guide policymakers and civil society organisations involved with digital policymaking in the direction of a more equitable and democratic digital environment, where basic liberties and rights are protected, where strong public institutions function in the public interest, and where people have a say in how their digital environment functions.

We established four guiding principles that can be applied to all layers of the digital space, from the physical networking infrastructure to the applications and services running on top of the infrastructure and networking stack. And they can also be applied to the social, economic or political aspects of society undergoing digital transformation. They are:

- Enable Self-Determination,

- Cultivate the Commons,

- Decentralise Infrastructure and

- Empower Public Institutions.

Now with this new project, we are saying that interoperability should primarily be understood to enable interactions between public institutions, civic initiatives and their audiences, without the intermediation of the now dominant platforms. Seen in this light the purpose of interoperability is not to increase competition among platform intermediaries, but to contribute to building public infrastructures that lessen the dependence of our societies on these intermediaries. Instead of relying on private companies to provide infrastructures in the digital space that they can shape according to their business model needs, we must finally start to build public infrastructures that are designed to respond to civic and public values underpinning democratic societies. In building these infrastructures a strong commitment to universal interoperability based on open standards and protocols can serve as an insurance policy against re-centralisation and the emergence of dominant intermediaries.

These public infrastructures do not emerge by themselves; they are the product of political and societal will. In the European Union, the political climate seems ripe for creating such a commitment. As evidenced by the current flurry of regulation aimed at the digital space, the European Commission has clearly embraced the view that Europe needs to set its own rules for the digital space. But if we want to see real systemic change we must not limit ourselves in regulating private companies (via baby steps towards competitive interoperability and other types of regulation) but we must also invest in interoperable digital public infrastructures that empower public institutions and civil institutions. If European policymakers are serious about building the next generation internet they will need to see themselves as ecosystem-builders instead of market regulators. Understanding interoperability as a generative principle will be an important step towards this objective.

How can people get involved and find out more?

People can reach out to us through our Twitter account: @SharedDigitalEU, they can write to us via email at hello@shared-digital.eu, or they can stay in touch through our newsletter, which we send out a couple of times per year.