What is a platform and when does it require regulation? Just as lawmakers in Brussels are beginning to seriously grapple with this question, researchers at the University of Amsterdam have published a paper on the evolution of the free-to-play shooter game Fortnite into a content delivery platform and its potential for manipulation.

What the researchers identified are two mutually reinforcing trends that blur the lines between certain online games and traditional platforms: by curating in-game events, adding social-media-like features and enabling increasingly sophisticated player interaction, games have the potential to become platforms in all but name, giving developers and third parties an engaging, new channel for the delivery of paid content and services, which can range from pop music concerts and movie trailer premieres to political campaigns.

Modern games can also play with our expectations, emotions and needs in ways that elude other means of expression. At their best, this makes games a powerful medium for introspection, education and social commentary. At their least ethical, it reveals the lengths to which some designers will go to manipulate their hyper-engaged audience – from Freemium titles that artificially limit and time content to induce FOMO (the fear of missing out), to addictive in-game microtransactions that resemble gambling in all but name.

What makes these trends more concerning is that the global gaming industry is exhibiting the tell-tale signs of ‘platformisation’ even at the macro level. Having experienced a period of democratisation and significant growth on the production side in the late 2000s and early 2010s – consider, for example, the advent of app stores and the renaissance of indie games – we are today seeing a period of heavy consolidation and centralisation of market power. And just as in other segments of the tech and creative industries, the new gatekeepers of gaming are engaged in winner-takes-all battles for attention, data, monetisation and intellectual property.

Why Europe is losing out

Widely recognised as one of the world’s fastest-growing industries, some estimates see the gaming sector turning over as much as $300 billion by 2025. Already today, games significantly outpace the global film and music industries. While the EU is a major consumer market for games, with revenues in excess of €21 billion in 2019 alone, it lacks the corporate heavyweights that dominate the industry in Asia and North America. As in other segments of the technology sector and creative industries, Europe boasts a rich tapestry of world-class developers and innovators but is home to few of the major studios or publishers and, at best, plays a supporting role in the development of gaming hardware, services and infrastructure. With the loss of the UK’s exceptionally strong gaming sector – which gave birth to Tomb Raider and Grand Theft Auto – to Brexit, it’s fair to say that Europe risks once again falling behind the big and, in China’s case, emerging players – a familiar refrain in the Tech Cold War.

Making Europe competitive in gaming will require greater support and smarter, forward-thinking regulation at the transnational level. Until relatively recently, the politics and regulation of video games were largely under the purview of national governments. Like many other areas of cultural and media policy, EU Member States tend to treat video games as a national competence. Often that means that countries have to go it alone when they feel the need to regulate, as Belgium did with its recent ban on loot boxes in games. But as online gaming and digital distribution are becoming the norm, it’s no longer possible to ignore the medium’s borderless nature and geopolitical relevance. Brussels needs to be prepared to deal with the looming challenges of the industry.

Through the technology glass

One solution is to look at gaming through the prism of platforms, technology and data policy, rather than just media and creative industries policy. This makes sense for several reasons. Firstly, on topics like Europe’s ‘digital sovereignty’ or the future of AI, the institutions in Brussels have finally come to terms with the idea that digital, competition and foreign policy are inextricably intertwined. As with data governance or social media regulation, it makes sense to view video games in the same context of Europe’s systemic competition with the Chinese and U.S. digital economies.

Secondly, large swathes of today’s gaming industry are owned, controlled or gate-kept by a small number of dominant and data-hungry technology companies, many of which are U.S. or China-based. That is a notable change from the early days of gaming when the industry was shaken up by garage start-ups, medium-sized toymakers, slot machine operators and manufacturers of HiFi equipment.

Lastly, gaming is plagued by many of the same transnational issues that we’re dealing with in technology and data policy. The gaming sector, too, struggles to contain the power of platforms, ensure fair competition, curtail the amplification of harmful content and champion data protection. Its concerns, too, include the manipulation of online marketplaces, foreign takeovers and the security and safety of products and services.

A ‘platformer’ as a platform is a platform

As the University of Amsterdam paper shows, a small sub-segment of games can – and probably should – be considered content delivery platforms. Sticking with their example, Fortnite is not so much a game in the traditional sense as it is an adaptable infrastructure that allows its developer Epic Games to deliver content and services, including advertising and product placements, to players in a highly engaging and immersive way.

Despite being nominally free-to-play, Fortnite operates its own marketplace and in-game currency. It generates billions of dollars in microtransactions and even manages to mobilise its players to express their political support for developer Epic’s antitrust disputes. It also boasts around 350 million registered players, an unknown but no doubt significant percentage of which are underage. In sheer numbers, that puts it on par with Twitter’s 330 million users. Unlike Twitter, however, Europe’s political class has taken relatively little notice of what’s going on over at Fortnite.

Trying to target Fortnite with ex-post regulation in 2021 would be missing the point. The game has been around for over three years, a lifetime in a fast-moving industry. It’s also just one highly-visible example of symptoms that affect an increasingly ‘platformised’ and politicised industry. Take PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG), a popular South Korean eSports title that goes heavy on microtransactions and has been downloaded a respectable 800 million times.

Because PUBG’s mobile version was co-developed by China’s Tencent, India recently moved to ban the game, describing it, alongside TikTok and a host of other Chinese apps, as a threat to the country’s ‘sovereignty and integrity’. In response, PUBG’s South Korean developers felt compelled to end their collaboration with Tencent in India.

There’s no immediate appetite in the EU to replicate such politically fraught measures, but the steady escalation of the Huawei controversy has shown that international political pressure to sanction tech companies can build up quickly and India’s decision on PUBG demonstrates how geopolitical context matters. In a country still set to bring more than 600 million of its citizens online, mobile games are a huge driver of smartphone adoption. Putting them under the microscope as vectors for soft power, economic exploitation and cyber attacks seems not entirely unreasonable.

Won’t somebody please think of the children?

Whether or not they would accept their classification as platform providers, it’s fair to say that the better-resourced publishers and gaming service providers have become more mindful of their responsibilities when it comes to ‘traditional’ online harms, particularly safeguarding minors. The rallying cry of “protect the children” – whether that’s from gratuitous violence, too much screen time or online grooming – has been a depressing constant in the politics of video games for decades, even if the evidence base often remains shaky.

Responding to a proliferation of national-level initiatives to regulate social media and online services after 2016, the gaming industry in Europe was quick to differentiate itself from traditional platforms, emphasising its responsible business practices and comparatively functional self-regulatory regime. Amping up their efforts to protect minors, who generally make up a larger share of the user base in games than they would on platforms like Facebook, the industry has been pushing its own online safety codes, educational campaigns and parental controls. Some platforms have rolled out automated flagging of suspicious online conversations to tackle grooming and online child sexual exploitation.

Playful propaganda

But as gamers get older – the average age of video game players in the EU is 31 years – and the industry finds itself at the centre of geopolitical competition, other ‘online harms’ are likely to come into focus. In 2019, Reporters without Borders released the Uncensored Library, essentially a Minecraft server granting in-game access to banned journalistic articles in an attempt to evade internet censorship in countries where Western social media channels were banned. Although laudable on its own terms, the project highlights how video games can become vectors and catalysts for political speech and even propaganda, a complex phenomenon that deserves a differentiated policy response.

Concerns over radicalisation loom especially large. At least since the Gamergate controversy of 2014, there is an implicit assumption that gaming subcultures skew towards digitally-native, hyper-engaged adolescent males with extreme views, a combination of characteristics often targeted by Russia’s Internet Research Agency and other state-sponsored troll farms. On the whole, that characterisation doesn’t hold true. Gamers are a more diverse and representative crowd than we give them credit for, and the stigmatisation of players as violent, at-risk individuals or misogynist shut-ins is more counterproductive than helpful when trying to identify or address the issue.

As a recent paper by the Radicalisation Awareness Network points out, public debate on the relationship between games and radicalisation – stoked after far-right attacks in Christchurch, Halle and El Paso – tends to oversimplify and conflate distinct issues. Games that are designed as propaganda tools, such as Hezbollah’s Special Force, will require a different response than the use of gaming-adjacent communication tools by radicals. Similarly, the use of gaming-cultural references by extremist sympathisers is not quite the same as the application of game design principles to terrorist recruitment, as exemplified by virtual scoreboards for ‘successful’ attacks. If policymakers in Brussels are serious about curtailing challenges like radicalisation, grooming and misinformation on the internet, then a good evidence base on the relationship of these issues with games should be the priority – preferably before reductive media narratives take hold and limit their scope to act.

States of play

Data flows and foreign takeovers present another contentious issue worth examining in this regard. Online games, and mobile games, in particular, are becoming an increasingly important source and beneficiary of data harvesting. As state or state-owned actors are beginning to invest in video games on a large scale, their ties to the industry are inevitably going to raise questions about the downstream use and potential abuse of gaming data. It’s easy to see how an increasingly state-sponsored gaming landscape could have a similarly destabilising effect on public trust as the arrival of Russian TV and Chinese tabloids had on the Western media ecosystem in the 2010s.

Indeed, the biggest area of concern seems to be China’s meteoric rise in the games industry, which makes as much sense economically as it does in terms of strategic data access. With investments in over 300 gaming companies, Tencent has rapidly become the world’s biggest video game publisher. Allegations of data-sharing between the tech giant and the Chinese government have already been the subject of occasional criticism, but its stakes in gaming companies with significant data assets, including Fortnite developer Epic Games and eSports giant Riot Games, are likely to receive more scrutiny going forward.

Whether data is genuinely at risk in these cases may almost be beside the point. If Europe wants to rekindle the public’s trust in data-sharing and the digital economy, its regulators and policymakers will have to become much better at anticipating, understanding and addressing data and takeovers issues in the games industry.

Playing to win

These problems extend beyond games that function like platforms themselves. Even ‘offline’ titles or online games that don’t quite fit the description of ‘quasi-platform’ tend to be inextricably linked to services that do. Plug-and-play is a thing of the past. In today’s video game economy, players have to interact with external platform providers that distribute games, enable access to additional content, track and broadcast their achievements, connect them to other players across the world and allow eSports enthusiasts to cheer for their favourite pro gamers.

Fortnite’s success, for example, is enabled by a platform-powered ecosystem that includes, but is not limited to, the developer’s own Epic Games Store, Twitch, Steam, YouTube, Playstation Network, Microsoft’s Xbox Live and Store, and many others. Pending a European antitrust complaint as well as several lawsuits, the iOS App Store and Google Play Store may or may not be added back to that list eventually. Last summer, both Apple and Google pulled Fortnite for breaching store policies when Epic tried to circumvent their in-app purchasing systems, which funnel 30 cents on every dollar made to Cupertino and Mountain View respectively.

Zooming out to the macroeconomic level, the Epic feud becomes just one of the many battles over platformisation, centralisation and anti-competitive practices that are set to define the next decade in gaming.

The effect of platform economics on games is equally obvious in the context of more open systems like the PC. Digital distribution is well-established and largely driven by bonafide platforms like Valve’s Steam store. It has cut out most of the middlemen and almost completely collapsed the second-hand economy. With packaging, discs, transportation, logistics and brick-and-mortar retailers out of the equation, publishers are seeing more money for their product and consumers get instant access to software from the comfort of their own home. Controversially, however, Steam – operated by a company that only employs around 360 people – takes a 30 per cent cut on every game sold through its platform. Much like Apple and Google, it has become a gatekeeper and quasi-essential infrastructure for PC gamers.

The list of grievances associated with Steam, and digital distribution more generally, reads eerily familiar to platform critics everywhere: asymmetrical contractual agreements with developers and publishers, unfair trading practices, data mining, targeted advertising, fake reviews and intransparent search algorithms that often dictate whether small-time developers get any consumer exposure at all. But 17 years into its existence, the Steam model is unlikely to change. Policymakers should focus on what’s next.

The next big thing

Among the handful of remaining players in digital distribution on PC, a familiar winner-takes-all mentality has taken hold. Would-be competitors need serious financial heft. Perhaps it’s therefore not surprising that Steam’s most serious challengers are backed by some of the world’s most valuable companies: Tencent is going head-to-head, while Microsoft, Apple, Google and Facebook are all looking to disrupt the digital distribution model in their own ways.

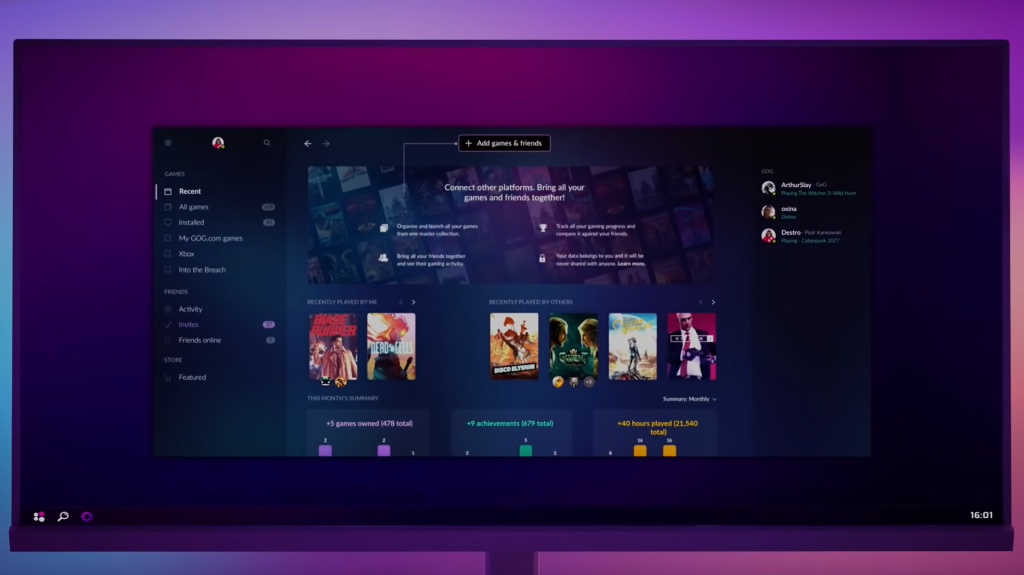

Europe, as in most other areas of the tech industry, sees itself relegated to the roles of consumer and supporting act. GOG, part of Poland’s CDProjekt Group, provides gamers with a relatively traditional store experience and boasts some laudable principles, such as integration of competitor platforms, DRM-free ownership of software and fairer treatment of developers, but it has so far struggled financially.

Tencent’s bid to corner the market comes courtesy of the Epic Games Store which, boosted by a cash injection from the tech giant and soaring Fortnite revenues, launched in late 2018. Intent on carving out a significant piece of the market before it’s too late, the service adopted an aggressive strategy: to lure in potential customers, it has given out at least one free game every week since launch – totalling more than 749 million giveaways in 2020 alone. In addition, Epic has signed a host of expensive exclusivity deals that prevent other distribution platforms from selling popular titles.

Across the Atlantic, perhaps the most serious attempt at shaking up the gaming market comes from Microsoft. Redwood pursues a more ambitious and novel business model than Epic, but at its core, it employs a similarly predatory pricing strategy. By moving its own game catalogue and dozens of licensed titles to the Xbox Game Pass, Microsoft combines a heavily subsidised, monthly subscription model with an opaquely curated selection of games. It also integrates the offering with its Microsoft Store, Xbox Live network and xCloud on-demand gaming service. Not content with limiting its ambitions to just one hardware base, Microsoft provides the service to Xbox consoles, PC and mobile devices, all of which can be covered with a single subscription. If Fortnite is a quasi-platform, Xbox Game Pass is designed to become a hyper-platform, and its strategy raises questions for consumer choice, competition and privacy.

Whoever emerges victorious from the war over digital distribution, both consumers and innovators will likely suffer in the long term. Players may at first rejoice at the idea of a weekly giveaway or a ‘Netflix for games’, but will eventually find themselves trapped in yet another walled garden. Developers and creatives, in turn, may hope to strike gold through greater and more targeted exposure on a highly centralised platform, but they too will find themselves at the whim of largely unaccountable and self-interested gatekeepers. Smaller competitors will struggle to gain traction or survive, as aggressive pricing strategies will always favour the giants, whose access to consumer data and endless lines of credit enables them to take and hedge long-term risks.

What’s left to play for?

After more than a decade of platform economics, the dynamics shaping today’s gaming industry are easy enough to spot. Their consequences may not always be predictable, but on balance they are likely to perpetuate the the same inequalities that we observe in the digital economy at large, further centralising power and profits in the hands of fewer market actors.

The stakes in this new theatre of the ‘Tech Cold War’ are high and, as in

other sectors of the digital economy, Europe is at risk of not just losing out

economically. In gaming, it could lose in a race for soft power at home and abroad. An

overly passive Europe risks becoming a rule-taker, rather than a standard-setter; a

captive consumer, rather than an innovator and market-shaper; and, in the parlance of

privacy, a data subject, rather than a data controller. Not every excess of the

industry will require disruptive, top-down regulation from Brussels. But policymakers

across Europe would do well to spend more time reflecting on games and where the

medium is headed.